12 Reasons You Need to Read Your Bible

Critical biblical scholarship is irreplaceable. But even when you do this, there are 12 reasons you still need to read your Bible.

Critical biblical scholarship is irreplaceable. But even when you do this, there are 12 reasons you still need to read your Bible.

Online education can readily foster spiritual formation because language always mediates formative presence and spiritual formation is a language game.

Faithlife has launched a new journal specifically for faculty, Didaktikos, which focuses on issues related to theological education.

Since the last time I mentioned the Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism, several new articles have been posted to the 2016 volume. These are: Preston T. Massey, “Women, Talking and Silence: 1 Corinthians 11.5 and 14.34-35 in the Light of Greco-Roman Culture Hughson T. Ong, “The Language of the New Testament from a Sociolinguistic Perspective” Jonathan M. Watt Geneva, “Semitic Language Resources of Ancient Jewish Palestine” Stanley E. Porter, “The Use of Greek in First-Century Palestine: A Diachronic and Synchronic Examination” For context, the latter three essays are introduced by the additional entry “The Languages Of First-Century Palestine: An Introduction To Three Papers.” ...

Mike Aubrey has provided an excerpt from an essay of his in Linguistics & Biblical Exegesis (Lexham, 2016). The excerpt strives carefully to work out a middle ground that is neither wholly on the side of theological lexica nor on that of James Barr’s critique of them. ...

Kirk Lowery has recently rebooted his blogsite, The Empirical Humanist, with entries thus far on topics including manuscript transcription, Google indexing, and (of course) language. ...

Steve Runge has a good introduction to the question of contrast and conjunctions’ relationship to it. Overall, conjunctions “do not create contrast that wasn’t already there, they simply amplify it. If there is no contrast present, using a contrastive conjunction is infelicitous as the linguists say. It comes across as wrong.” For more, see Steve’s original post. ...

Grammar of Biblical Hebrew Fred Putnam’s New Grammar of Biblical Hebrew is now out ( affiliate disclosure). According to the publisher, This is a Hebrew grammar with a difference, being the first truly discourse-based grammar. Its goal is for students to understand Biblical Hebrew as a language, seeing its forms and conjugations as a coherent linguistic system, appreciating why and how the text means what it says—rather than learning Hebrew as a set of random rules and apparently arbitrary meanings. ...

This week in the biblioblogosphere: Mark Goodacre finds and makes available a PDF version of Wilhelm Wrede’s Paul. Daniel and Tonya draw attention to Alex Andrason’s recent article on the use of yiqtol in Biblical Hebrew (via Uri Hurwitz) and Randall Buth’s response to the article. Via Ekaterini Tsalampouni, Holger Szesnat mentions the availability of the new Journal of Ancient Judaism. Christian Askeland notes the availability of a stable, Unicode-compliant Coptic font. At BioLogos, Peter Enns interviews N. T. Wright about Jesus’ humanity. Kirk Lowery ponders current developments in the peer review process for scholarly publications. Scot McKnight prepares his readers for a change of blogging address. Larry Hurtado uploads an essay on Martin Hengel’s impact on English-speaking, New Testament scholarship. Charles Halton considers cartographic hermeneutics and some of their implications for readers of biblical texts.

The equivalent of 15 print volumes of over 1,800 Oxyrhynchus Papyri fragments are now available to order from Logos via their pre-publication discount program. Details about the module and a list of the papyri it will include are available here. ...

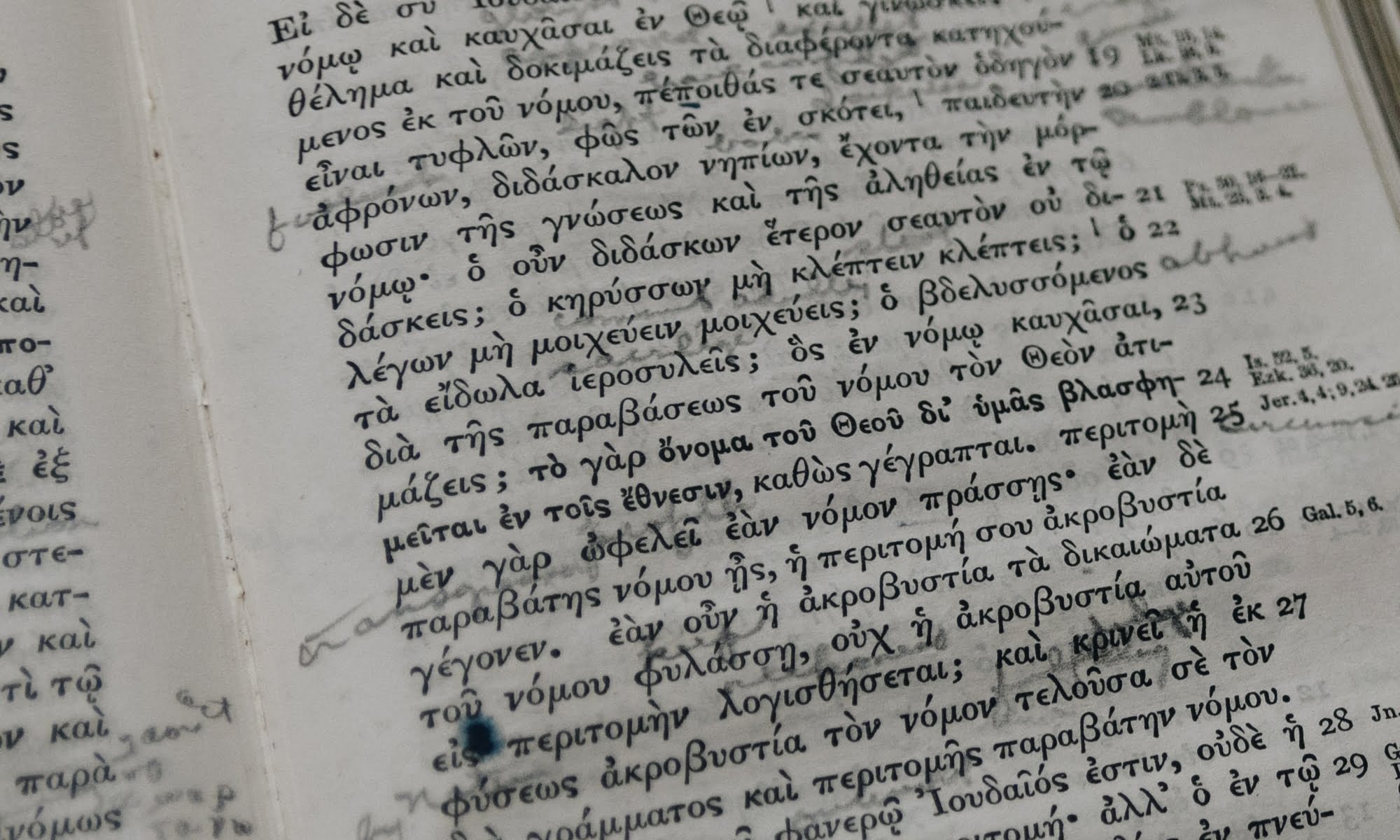

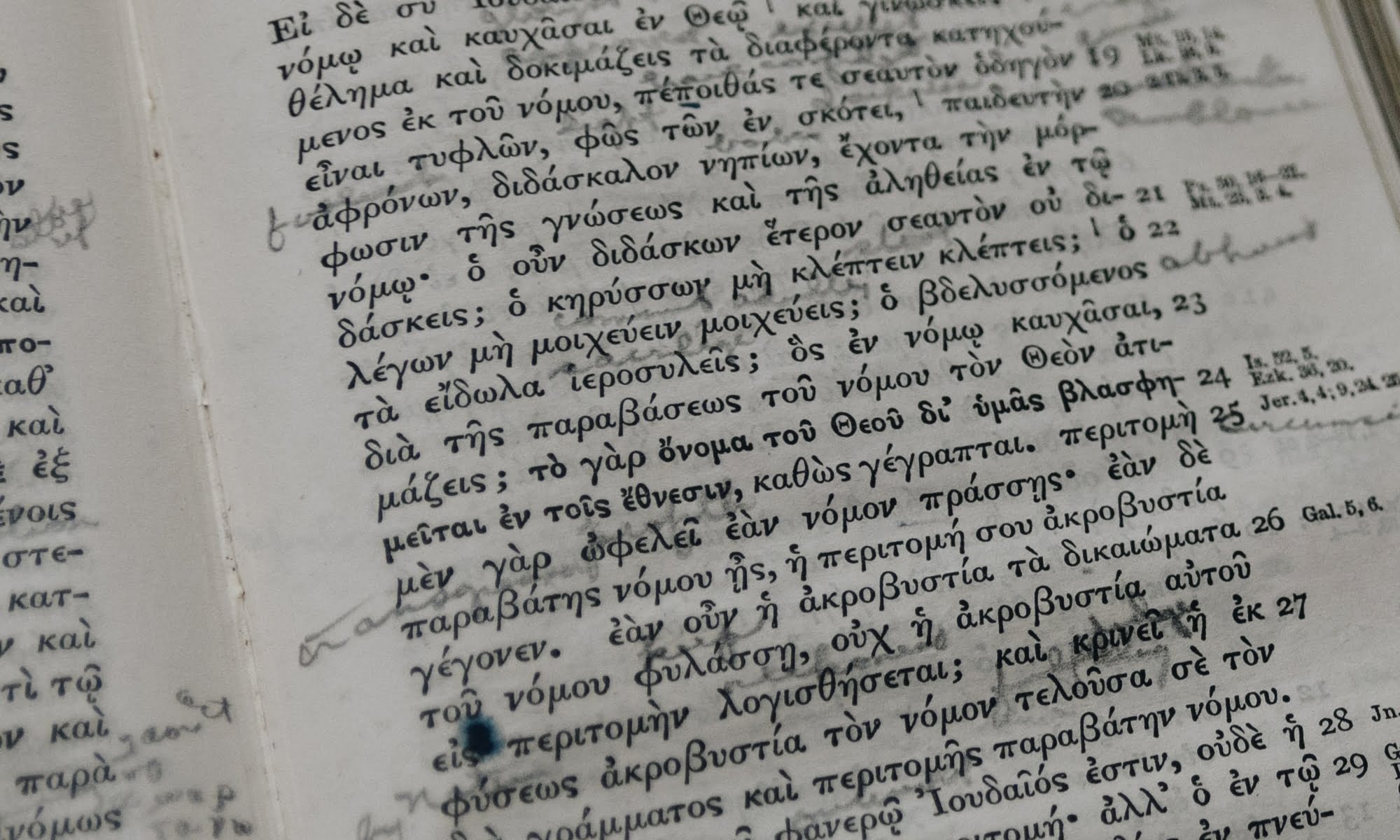

Despite the imperial connection that might have been expected to promote the Latin tongue, “[e]ven after Rome became the world power in the first century BCE, Greek continued to penetrate distant lands. (This was due largely to Rome’s policy of assimilation of cultures already in place, rather than destruction and replacement.) Consequently, [when Pompey conquered Palestine in 63 BC ( Ferguson 411) and] even when Rome was in absolute control [under Augustus in 31 BC-AD 14 (cf. Ferguson 26–30)], Latin was not the lingua franca. Greek continued to be a universal language until at least the end of the first century” ( Wallace 18). Moreover, when one considers the strong Jewish presence in Palestine, it becomes clear that Hebrew and Aramaic would constitute important languages in the Palestinian milieu (cf. Poirier 55). ...

The linguistic situation in Palestine during the first century AD was, to say the least, quite complex because it involved interaction among four different languages—namely, Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, and Latin. The presence of other languages is also apparent, and although few individuals were probably fluent in three or more of these languages, many were probably bilingual ( Poirier 56). In seeking to understand this multi-faceted situation, our strategy will be to handle the less common languages first and proceed to the more common ones. Although language distribution “varied almost personally” ( Poirier 56, quoting Barr 112), of primary concern will be the question: Which language(s) held vernacular or nearly vernacular status? ...