If you’re writing in biblical studies, you need to be able to type biblical languages.1 Transliteration works sometimes. But you can’t and shouldn’t bank on always using transliterations. Because of that, you need Unicode.

Why Unicode Is Important

In years gone by, typing biblical languages on an English keyboard meant using a font that would mask English text. If you had the proper font installed and selected, your text would look like Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek.

If you didn’t, it would look like a string of nonsense English characters. For instance, “λόγος” would display as “lo/gov”.

For Hebrew and Aramaic, this situation also meant you had to type the text backward (i.e., left to right in the direction of English). And if you wanted to submit a paper electronically, you’d need to ensure you used the proper font or included the proper font with your paper.

Thankfully, Unicode has changed all this.

What Unicode Does

Unicode “provides a unique number for every character, no matter what platform, device, application or language” is used.2

These unique numbers—like 03C2—might not mean much to you. But they allow computers to tell exactly what character is being used. And importantly, Unicode allows computers to make this determination independent of the font you’re using.

For instance, a computer knows 03C2 represents a human-readable final sigma (ς) and not a Hebrew vav (ו). In by gone days, you might well have typed both with the v on an English keyboard. But as long as you’re using a font that can handle Unicode, your computer will know which character is which.

So, you can change the font however you like (e.g., Arial, SBL BibLit, Times New Roman). Your biblical-language text will remain readable, as will your main prose.

If this all sounds a bit too technical, just remember that, with Unicode, a sigma is a sigma, a vav is a vav, and changing fonts doesn’t change that.

That text remains readable when you change fonts or send the file to someone else. If that person doesn’t have your font, the computer might substitute a different one, but it shouldn’t display gibberish.

How to Install a New Keyboard, or Keymap

To begin typing biblical languages in Unicode, you need some software to help. You can find this available freely online or, with perhaps more limited functionality, as features within your operating system (e.g., Mac, Windows).3

Personally, I’ve preferred and used the keyboards provided by Logos (affiliate disclosure) and Tyndale House.

Logos

The Logos keyboards are available for Greek, Hebrew-Aramaic, Coptic, Syriac, and transliteration.

You don’t need a Logos base package to use these keyboards. They’re free and independent of Logos itself. So, you can even use these software keyboards if you use another Bible software altogether.

You can download and install whichever keyboard combination you prefer. Inside each ZIP download is a PDF showing exactly what key strokes or combinations will produce what Unicode characters.

Additional Considerations

Most keyboards should install pretty simply by following the instructions provided (affiliate disclosure). There are two possible exceptions, however:

- For a right-to-left language (e.g., Hebrew), you may need to reboot your computer or allow it to install support for right-to-left (or “complex script”) languages in order to use that keyboard.

- For the transliteration keyboard, you may end up with two English keyboards installed. To check this in Windows 11, search for “language” in the Windows menu, and open

Edit language and keyboard options. From there, check the keyboards you have installed for English. You can then remove the standard QWERTY layout. That way, you can simply use the more robust transliteration keyboard as your basic English keyboard, and you needn’t have a fourth keyboard in your way in the keyboard switcher.

How to Change Languages

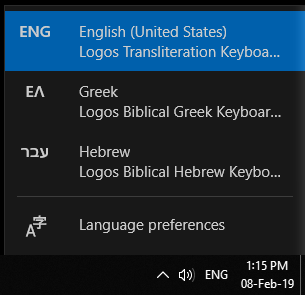

To use a particular keyboard layout in Windows 11, choose that layout from the language button that should appear in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen by the default clock position.

To use a particular keyboard layout in Windows 11, choose that layout from the language button that should appear in the bottom right-hand corner of the screen by the default clock position.

Or you can use the keyboard shortcut Alt+Shift. This shortcut will cycle through the keyboard layouts without an on-screen prompt. And you’ll quickly learn the order in which they come up.

When you’re ready to type in English again, simply change the keyboard switcher back to English, and you’re good to go.

Tyndale House

The Tyndale House keyboard supprots Greek and Hebrew-Aramaic. In addition to Windows and MacOS, Tyndale House also has a Linux installer.

In rare cases, you might find that the Tyndale House keyboards don’t support a particular character (e.g., 05C4, a combining, supralinear upper center dot over a Hebrew character). But you might prefer the Tyndale keyboard’s mappings. Or if you use Linux, the Tyndale House keyboard seems to be by far the most comprehensive such tool.

Tyndale House provides a compressed file installer for each supported operating system. This is a .zip file for MacOS and Windows and a .tgz file for Linux. Open this compressed folder, and follow the installation instructions in the Tyndale_Keyboards_for_\[youroperatingsystem\]_Installation_Guide.pdf.

Cardo Font

With these installation files, Tyndale House provides files for the Cardo font. Cardo is a serif font with quite full support for Greek and Hebrew-Aramaic text. So, if you’d like to try it, you can follow the Cardo installation instructions also.

But the keyboards will work fine with other serif fonts also (e.g., Times New Roman). Or you can pick any number of other sans serif fonts. After all, that’s part of the point of Unicode.

How to Change Languages

The Tyndale House keyboard installation guides also provide helpful, step-by-step instructions about switching languages. They also include a Tyndale_Keyboards_for_\[youroperatingsystem\]_Usage_Guide.pdf that shows you which characters will map to which keys on your keyboard.

Conclusion

Whether you’re just learning biblical languages or you’re pretty comfortable with them, being able to type them in Unicode will prove incredibly useful. It will help you communicate with others more clearly and simply about these languages.

Once you invest a few minutes in setting things up properly, you’ll be ready to write, and you’ll enjoy a much more seamless experience when using these languages in your writing.

-

Header image provided by Paul Zoetemeijer. ↩︎

-

The Society of Biblical Literature also has several resources that may prove helpful as you get set up for and used to typing in Unicode Greek, Hebrew, or Aramaic. ↩︎