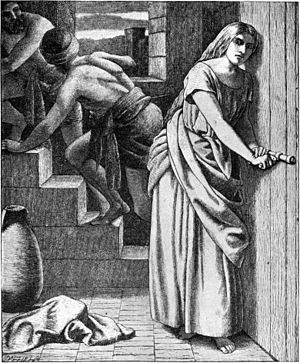

[caption id="" align=“alignright” width=“150” caption=“Rahab Helping the Two Israelite Spies (Image via Wikipedia)”]  [/caption]

[/caption]

After assuming leadership over Israel ( Josh 1:10–18), Joshua commissions two men to survey Jericho and the surrounding area ( Josh 2:1a). Rather tersely, then, the menוילכו ויבאו בית־אשׁה זונה ושׁמה רחב וישׁכבו־שׁמה ( Josh 2:1b; went and entered the house of a prostitute, whose name was Rahab, and they lodged there). For onlookers, such an action might not have been unusual in itself, 1 but by some means or other, the king became aware of these Israelite’s intent to survey Jericho ahead of some forthcoming military action ( Josh 2:3).

Even before the king’s messengers had arrived, however, Rahab had apparently become aware that they were coming and hid the Israelite spies ( Josh 2:4a, 6). While the spies are hiding ( Josh 2:8), 2 Rahab engages them in a brief exchange that solidifies both her promise of protection to them and their promise of the same to her and her family on certain conditions ( Josh 2:9–14). When Rahab describes the background for her actions, she twice acknowledges Jericho’s broad recognition of יהוה’s greatness ( Josh 2:9, 11a) because of what he had recently done for Israel in helping them against other peoples they had encountered before arriving at Jericho ( Josh 2:10, 11b). 3 Yet, only in Rahab’s case is this fear of יהוה said to translate into חסד ( Josh 2:12; kindly) acts, 4 to which the spies respond חסד ואמת ( Josh 2:14; kindly and faithfully; cf. Josh 2:17–20; 6:22–23, 25).

Rahab thus constitutes an example of one who both hears the report about יהוה’s mighty deeds and rightly credits that report, δεξαμένη τοὺς κατασκόπους μετʼ εἰρήνης ( Heb 11:31b; receiving the spies with peace; cf. Heb 4:2). Yet, alongside Abraham ( Jas 2:21–23), James sets forth Rahab as an example of one who is ἐξ ἔργων δικαιοῦται . . . καὶ οὐκ ἐκ πίστεως μόνον ( Jas 2:24; justified from works and not from faith only; cf. Jas 2:25–26). It is difficult to assess whether James sees Rahab’s deception of the king’s men ( Josh 2:3–5) as an endemic component of her kindness toward the spies (cf. Josh 2:14) or as deception that יהוה presumably forgave within the context of her faith in him (cf. Gen 20:1–13; 26:6–11). 5 What is clear, however, is that, in Jas 2:14–20, δικαιοῦσθαι ἐκ πίστεως μόνον refers to something like “being justified for fine words while sitting on one’s hands.” Fine words acknowledging יהוה’s greatness Rahab certainly does have ( Josh 2:9–13), but James holds her forth as an example because her fine words, as faithful words, are a genuine testimony of one piece with her ὑποδεξαμένη τοὺς ἀγγέλους καὶ ἑτέρᾳ ὁδῷ ἐκβαλοῦσα ( Jas 2:24; having received the messengers and sent them out by another way). 6 Indeed, in so doing (cf. Josh 6:25), Rahab the sinner received the Israelite men and kept them from harm, 7 and thus, Rahab came to stand in the line of the Israelite man who receives sinners and keeps them from harm (cf. Matt 1:5; Luke 15; John 9:1– 10:18). 8

1. Bird, “The Harlot as Heroine,” Semeia 46 (1989): 128; Keil, Joshua, 26.

2. First Clement 12 ( ANF, 1:8); Keil, Joshua, 27, regard Josh 2:8 as a reference to the spies’ going to sleep. Yet, because the preceding context says that the men had gone to the roof to hide ( Josh 2:6), Josh 2:8–14 might be understood as a flashback or as Rahab’s later discussion with the men in which she discloses convictions she had already held (cf. McCartney, James, 171).

3. Chyrsostom, Hom. Heb., 27.3 ( NPNF1, 14:487–88), suggests that the spies themselves brought to Rahab the news of what יהוה had done for Israel. If such were the case, then their possible communication of this news to others also might have been the reason that they attracted such unfavorable attention and that the king became aware of their presence at Rahab’s house. Yet, such a reading would present a difficulty with Joshua’s original commission of the men to perform their reconnaissance חרשׁ ( Josh 2:1; secretly).

4. Cyril of Jerusalem, Paen., 9 ( NPNF2, 7:10); Ephraim Syrus, The Pearl, 7.1 ( NPNF2, 13:299), suggest Rahab as a model of Christian repentance. See also Augustine, Enarrat. Ps., 87.5 ( NPNF1, 8:421–22); Cyprian, Epist., 75.4 ( ANF, 5:398); Jerome, Epist., 52.3 ( NPNF2, 6:91).

5. Augustine, C. mend., 32 ( NPNF1, 3:495–96), strongly prefers this later possibility.

6. Cf. 1 Clem. 12 ( ANF, 1:8); Ambrose, Fid., 5.10.127 ( NPNF2, 10:300); Beale, New Testament Biblical Theology, 520–22.

7. Westcott, Hebrews, 377.

8. Cf. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God, 264–74.