While reading around Justin Martyr’s First Apology this morning, I came across a few interesting points.

Historical In discussing the injustice of Christians’ condemnation, Justin says,

By the mere application of a name, nothing is decided, either good or evil, apart from the actions implied in the name; and indeed, so far at least as one may judge from the name we are accused of, we are most excellent people. But as we do not think it just to beg to be acquitted on account of the name, if we be convicted as evil-doers, so, on the other hand, if we be found to have committed no offence, either in the matter of thus naming ourselves, or of our conduct as citizens, it is your part very earnestly to guard against incurring just punishment, by unjustly punishing those who are not convicted. For from a name neither praise nor punishment could reasonably spring, unless something excellent or base in action be proved. And those among yourselves who are accused you do not punish before they are convicted; but in our case you receive the name as proof against us, and this although, so far as the name goes, you ought rather to punish our accusers. For we are accused of being Christians, and to hate what is excellent (Chrestian) is unjust (Justin, 1 Apol. 4; emphasis added).

In this section, Justin makes rhetorical use of the identification of Christians as followers of Chrestus (see Suetonius, Claud. 25; χρήστος ≈ “excellent, worthy, good”) in order to establish his two-fold claim that: (1) Christians should be judged by their works rather than by their name and (2) even if they are judged by their name, they should receive approval.

Lexical Justin reports that, when a congregation gathered to share the Eucharist, the “president of the brethren” would offer “prayers and thanksgivings,”

And when he has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all the pople present express their assent by saying Amen. This word Amen answers in the Hebrew language to γένοιτο" (Justin, 1 Apol. 65; emphasis added).

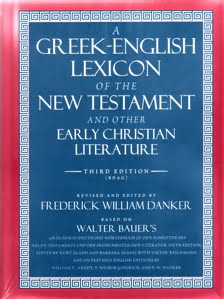

BDAG, of course, already contains this reference in the entry for ἀμήν, yet another anecdotal reason to read whole lexical entries.

Theological Continuing in his description of the Eucharist, Justin explains that

And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh. For the apostles, in the memoirs composed by them, which are called Gospels, have thus delivered unto us what was enjoined upon them; that Jesus took bread, and when He had given thanks, said, “This do ye in remembrance of Me, this is My body;” and that, after the same manner, having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, “This is My blood;” and gave it to them alone. Which the wicked devils have imitated in the mysteries of Mithras, commanding the same thing to be done. For, that bread and a cup of water are placed with certain incantations in the mystic rites of one who is being initiated, you either know or can learn (Justin, 1 Apol. 66).

To these remarks, the Ante-Nicene Fathers edition subjoins the intriguing comment from Gelasius, the fifth-century, Roman bishop, that “[b]y the sacraments we are made partakers of the divine nature, and yet the substance and nature of the bread and wine do not cease to be in them” (Justin, 1 Apol. 66 n. 6). Others may have more astute perspectives, but surprisingly, to my perception, given Gelasius’s Roman ties, Gelasius’s seems to favor something more akin to con substantiation (or something like it) than tran substantiatition. Of course, even on this reading, the extent to which Gelasius reflects well what Justin was intending to communicate remains debatable (see Justin, 1 Apol. 66 n. 6; Joseph Pohle, “The Real Presence of Christ”).

In this post:[caption id=“attachment_1984” align=“alignleft” width=“90” caption=“Walter Bauer, Frederick Danker, William Arndt, and Wilbur Gingrich”]  [/caption] [caption id=“attachment_2148” align=“alignleft” width=“130” caption=“Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Cox”]

[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_2148” align=“alignleft” width=“130” caption=“Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Cox”]  [/caption] [caption id=“attachment_3126” align=“alignleft” width=“80” caption=“Suetonius”]

[/caption] [caption id=“attachment_3126” align=“alignleft” width=“80” caption=“Suetonius”]  [/caption]

[/caption]

- Mike Aubrey, “You MUST use BDAG”

- Joseph Pohle, “The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist”