Academic New Testament studies sits at the crossroads of various disciplines.1 History, rhetoric, social sciences, linguistics, lexicography, and textual criticism are just a few.

Each of these disciplines has its own voluminous secondary literature. Even once you specialize into a particular New Testament book or corpus, the amount of secondary literature is still vast.

Familiarity with secondary literature is critical. But while working through all the secondary literature (not to mention navigating other things vying for your attention), it can be all too easy to not work regularly through the New Testament itself.

There are any number of reasons to resist this tendency. As you do, you can reap tremendous benefits from what’s “above the line” in a modern, critical edition’s main text. There’s also huge value in what’s “below the line” in the critical apparatus and in the original manuscripts themselves.

Reading the Main Text of Your Greek New Testament

With what’s “above the line,” I’d like to focus on three reasons you need to regularly read your Greek New Testament. These are, namely, to

- sharpen your Greek,

- observe the text more carefully, and

- decolonize yourself.

1. Sharpen Your Greek

Regularly reading the New Testament in Greek will help prevent all your hard work learning the language from going to rust. More than that, it will help you sharpen and improve your Greek.

Most basically, it will introduce you to new vocabulary or reintroduce you to vocabulary you only see infrequently. The same is true for grammatical constructions.

Of course, you can reinforce vocabulary by reviewing word lists or flash cards. Or you can cycle through grammars to stay abreast of syntactical material.

Both of these practices are also good. But continuing to internalize New Testament Greek by reading the New Testament has two advantages:

- Reading the New Testament gives you context. This context can help trigger your memory when reading other texts. And it will do so in ways that separate flash cards, word lists, or grammatical discussions won’t.

- Reviewing lexical and grammatical study aids only ever gives you the information in those aids. But those aids derive from the New Testament and don’t determine it. So, if you only (or mainly) work with study aids, they’ll cap the expertise you develop.

2. Observe the Text More Carefully

To say the least, when you read the Greek New Testament, you don’t always find what you might have expected. The translations you’re familiar with aren’t always transparent to how the text reads in Greek.

Reading the Greek text itself allows you to see connections—both at the word and at the phrase level—between different passages. It will also let you see when a connection might not actually be there.

For instance, the English Standard Version gives Rom 6:7 as “one who has died has been set free from sin.” Paul then later talks about “having been set free from sin” (Rom 6:18).

You could never suspect from the translation of v. 7 that one word is in use there (δεδικαίωται) while an entirely different one is in use in v. 18 (ἐλευθερωθέντες). Even if the two verses are talking about the same event, might they be talking about it in different ways? And if so, might that distinction be important?

These benefits can be even larger if you practice reading the text aloud as well and not just silently. Your ear will sometimes catch something that your eye will miss.

That experience of recognizing that something “sounds wrong” can be a valuable prompt to consider the text more closely and notice nuances you would otherwise have missed.

3. Decolonize Yourself

It’s been rightly observed that “All translation is colonization.”2 All translation, by definition, dresses up a text in clothes that aren’t native to it.

That reality can be helpful. It makes the New Testament accessible to billions of people who don’t read Greek and aren’t going to learn how.

That said, reading the New Testament in Greek has the upside of forcing readers to come to terms with it. The outcome might still be that you make your own translation, which would be its own kind of colonization.

But the process of coming to terms with the Greek text for yourself forces you to reckon with what you find there. It puts you in a much readier position to have “the experience of being pulled up short by the text.”3

And when the text does pull you up short—does break with what you expected of it—it’s there that it exercises its decolonizing counter force. It’s there that reckoning and wrestling with the text’s meaning helps loosen colonization’s grip on you and your encounter with the text.

Reading the Critical Apparatus of Your Greek New Testament

The apparatus to a critical text of the Greek New Testament condenses a wealth of information about the text.

The apparatus can be a bit complicated to get used to. The symbols and abbreviations it uses are their own kind of language that you need to learn, even aside from the language of the text.

In another respect though, the apparatus can also be deceptively simple unless you read it in two different ways—both vertically and horizontally. So, let me briefly describe both of these ways of reading the apparatus and then illustrate their differences with an example.

Reading Vertically

Reading the apparatus vertically is by far the more obvious of the two strategies. As you read the main text, you find different places of variation.

For each place of variation, you can then consult the apparatus to see what it has to say about the different witnesses it includes.

You then move on in the main text to the next place of variation, considering the various options it indicates for filling the place where it’s noted in the main text.

When you read your apparatus “vertically,” you consider the variants more or less in isolation from each other and look at their various, individual alternatives for the main text.

Reading Horizontally

If a text has fewer variants noted in your edition, the apparatus may have too little information for you to read it meaningfully in any way except vertically. But especially where a text has multiple places of variation noted, reading the apparatus horizontally is important too.

When reading horizontally, you read across the different places of variation to better understand the text’s different forms. For each place of variation, you’re looking for common (groups of) manuscripts that create patterns of attestation for different readings.

As you move from one place of variation to the next, you don’t pull the variations up into the main text (reading vertically). Instead, you simply use the main text to fill in the gaps in the apparatus as you continue reading horizontally there.

An Example of Reading Vertically versus Reading Horizontally

To illustrate the differences between reading vertically and reading horizontally, let’s take a text where the Nestle-Aland’s 28th edition (NA28) notes several places of variation, Rom 10:5.

Reading Vertically in Romans 10:5

In the NA28, this text appears as

Μωϋσῆς γὰρ γράφει ⸂τὴν δικαιοσύνην τὴν ἐκ [τοῦ] νόμου ὅτι⸃ ὁ ποιήσας °αὐτὰ °1ἄνθρωπος ζήσεται ἐν ⸀αὐτοῖς.

Reading vertically, you have five different places of variation noted in the text. The NA28 notes these places of variation with the signs ⸂…⸃, […], °, °1, and ⸀.

Reading Horizontally in Romans 10:5

This said, if you unpack the apparatus by reading it horizontally, you find that its compact citations of witnesses for these five places of variation actually identify eleven distinct readings for this one verse. The additional readings emerge because some witnesses group together differently at the different places of variation.

Basic Findings from Reading Horizontally

According to the apparatus, the differences in these readings mainly revolve around the

- placement of ὅτι, whether before τὴν δικαιοσύνην or after νόμου,

- presence or absence of τοῦ,

- interchange of νόμου and πίστεως,

- presence or absence of αὐτά,

- presence or absence of ἄνθρωπος, and

- interchange of αὐτοῖς and αὐτῇ.

But unless you read horizontally across the variation units, you might well miss that, for example, features 1 and 4 are strongly related.

Additional Observations from Reading Horizontally

When ὅτι appears after νόμου, it simply introduces the following quotation from Lev 18:5. In this case, δικαιοσύνην is an accusative of respect that tells the topic about which Μωϋσῆς … γράφει. The ὅτι clause then specifies the content of what Μωϋσῆς … γράφει.

But when ὅτι appears before τὴν δικαιοσύνην, it directly introduces the content of what Μωϋσῆς … γράφει. This means that αὐτά and δικαιοσύνην both want to be direct objects for the participle ποιήσας.

The verb ποιεῖν can sometimes take two accusative objects (e.g., “to make them [to be] the righteousness”).4 So, sometimes (33*, 1881) ὅτι appears and the manuscript has both τὴν δικαιοσύνην and αὐτά.

But this reading generally seems to have not been found preferable. So, in the rest of the cited witnesses where ὅτι appears before τὴν δικαιοσύνην, the text omits αὐτά. Arguably making the text more straightforward, this omission leaves δικαιοσύνην as the lone accusative object for ποιήσας (א*, A, D*, 81, 630, 1506, 1739, co).

Observing groupings like this can help in sorting out the different readings, possible reasons for them, and suggestions they may imply for how the text was understood.

Reading Original Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament

Your modern, printed or electronic Greek New Testament gives you fine critical text based on innumerable hours of careful scholarship.

But even with a text like this in hand, there still might be occasions where you’ll find it useful to work through a portion of an individual Greek manuscript.

Doing so will definitely present an additional challenge beyond reading a printed Greek text. Depending on a particular copyist’s handwriting and the condition of the manuscript, its text may be more or less legible.

Increasingly, you’re able to access digital images of manuscripts online. So, you’re not necessarily out of luck if you can’t travel to where a particular manuscript is kept. Often, the images you can get are stunningly high-quality. Other times, even the best online access to a manuscript may be a scan of comparatively low-quality microfilm.

Benefits of Reading Handwritten Manuscripts

However you’re able to access them though, trying to work through at least portions of these manuscripts has two key upsides by comparison with modern critical editions:

- For all the challenges of handwritten texts and their digitization, the manuscripts can sometimes be clearer than your critical apparatus. Looking at a manuscript gives you just what’s in that manuscript. It doesn’t try to compress it along with other witnesses like your apparatus does. So, if your apparatus looks confusing, you might be able to clarify it by consulting a scan of one of the witnesses it cites.

- A critical text is a selection by editors of what features are relevant to represent from which witnesses. That selection is learned and careful, but it’s still a selection. Going directly to an image of a manuscript may turn up some features that weren’t relevant for your critical edition but are still interesting. And at the very least, having a look at a copy of a manuscript on which your critical text is based will give you a better appreciation for the kind of things such manuscripts are, not to mention the kind of craftwork that goes into constructing a critical text from them.

For information about these manuscripts, as well as what you can access online, the database that the Institut für Neutestamentliche Textforschung (INTF) provides is the most complete, authoritative repository. But a good deal of this information is also making its way into Logos Bible Software.

How to Access Handwritten Manuscripts through Logos

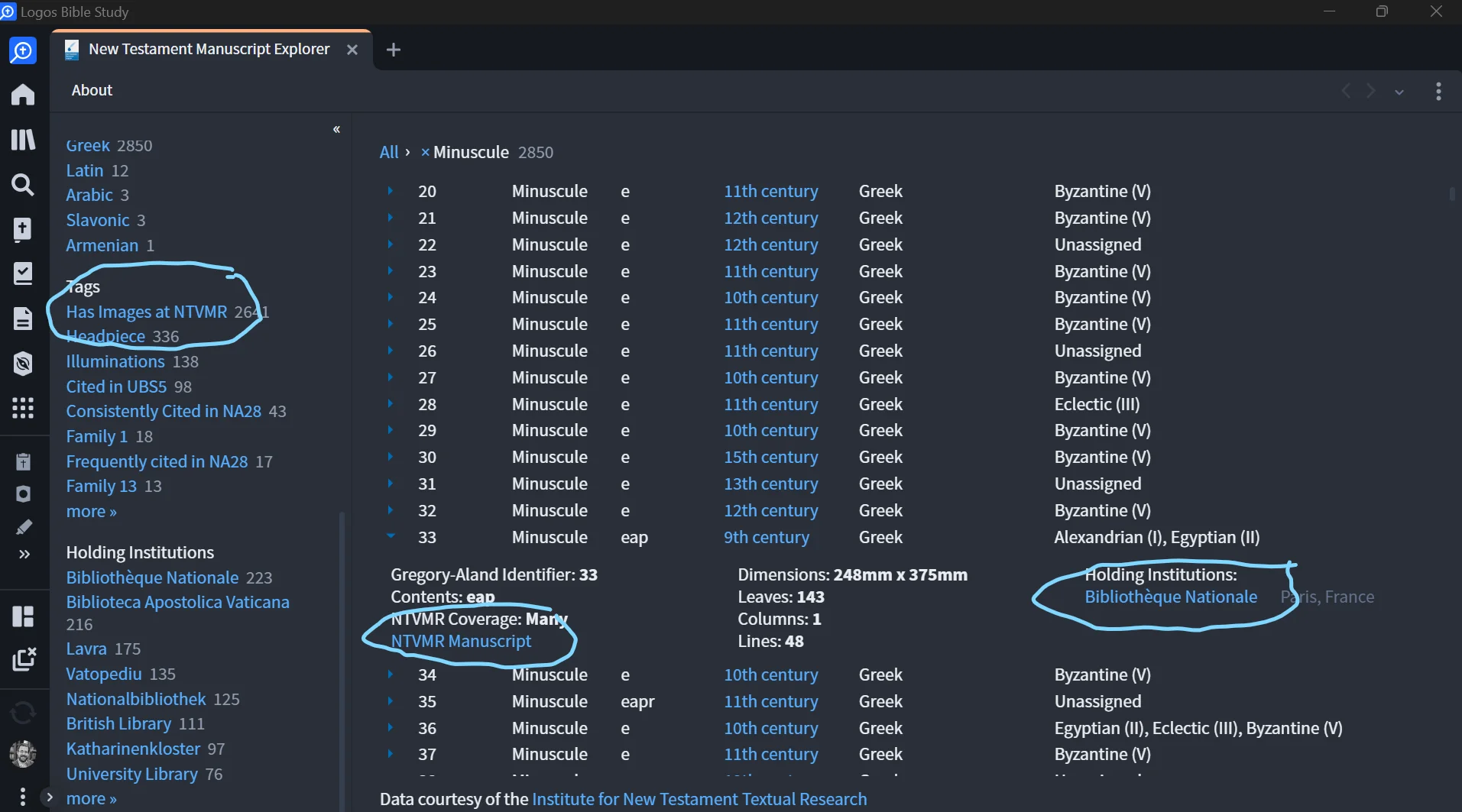

If you have Logos 10 Bronze or above (affiliate disclosure), you have access to the Greek New Testament Manuscript Explorer tool. (And yes, there are companion tools for the Hebrew Bible and its Greek versions.)

For each manuscript in it, the explorer provides a link to the holding institution’s website, where available. There, you might be able to find the manuscript, but the link in Logos will just take you to the institution’s main page.

When available for each manuscript in the explorer also, Logos provides an “NTVMR Manuscript” link. “NTVMR” is short for “New Testament Virtual Manuscript Room.” Clicking this link will send you straight to that particular manuscript on INTF’s website.

You’ll often need to obtain a user account and login to access the manuscript images. But even without these, you should be able to see the manuscript’s transcription and access its metadata, including any other places online where you might be able to view it, even without an INTF user account. (For more on exactly how to do this, see the INTF guide in this resource pack.)

In the Logos explorer, you can even click the “Has Images at NTVMR” tag to narrow the manuscript list just to those manuscripts for which Logos has direct links to page images at INTF.

Conclusion

Amid everything that’s vying for your time and attention, it can be all too easy to let days slip by without regularly diving into the Greek New Testament. But if you’ve developed enough skill to read it in the first place, it’s well worth protecting that investment and continuing to hone your skill by staying in the text.

As you do so, you’ll find that you notice things you otherwise wouldn’t and that the text pushes back on you, prodding you to hone your skill further. That happens mostly—and most conveniently—in the main text of your modern, critical edition. But it can definitely also happen as you’re working through that edition’s apparatus, or some portion of a handwritten manuscript.

Header image provided by Kelly Sikkema. ↩

Allan Persinger, “Foxfire: The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation” (PhD diss., University of Wisconsin, 2013), 11. ↩

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, ed. and trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall, 2nd ed., Bloomsbury Revelations (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 280. ↩

Leave a Reply