Academic biblical studies requires spending a lot of time in a wide variety of primary and secondary sources.1 And among these sources, the Bible itself is the most primary. So, it’s important to maintain a regular habit of reading it for at least 12 reasons—namely, to

- Remind yourself that biblical studies is about the Bible.

- Remind yourself that the Bible is Scripture.

- Encounter the word of God.

- Understand the biblical authors’ worldviews.

- See things you won’t by reading only isolated passages.

- Correct your reading of one passage against another.

- Focus more fully and hear things you won’t by reading silently.

- Sharpen your languages.

- Find things you won’t in translation.

- Notice scribal errors.

- Learn vocabulary.

- Enjoy the flow of reading in the original languages.

Of these, the first 7 apply whatever language you’re reading in. The last 5 are special benefits if you’re reading the Bible in its primary languages.

1. Remind yourself that biblical studies is about the Bible.

Much of academic biblical studies has to do with thinking critically about the biblical text. It has to do with bringing preconceptions into question and making judgments like historians. It has to do with looking closely at the text and its contexts again and again.

This work is good and important. Nothing can substitute for detailed, careful attention to a particular book, a given passage, or even a single verse.

But with this kind of close attention also comes the danger of paying so much attention to the individual trees that the forest fades from view.

There’s a risk of increasing your knowledge of a small slice of the biblical literature at the cost of increasing your unfamiliarity with other parts.

To counteract this tendency toward unfamiliarity, it’s helpful to cultivate a regular habit of Bible reading.

2. Remind yourself that the Bible is Scripture.

Not all biblical scholars claim membership in a particular faith community. Among those who do, not all see this membership as relevant to their scholarship. But biblical scholarship is a coherent discipline only because of the faith communities within which biblical texts emerged.

In practice, “Bible” might mean quite a lot of different things. It might be

- a “Hebrew Bible” without a New Testament,

- a “New American Standard Bible” with a New Testament but no apocrypha, or

- a “New Jerusalem Bible” with both a New Testament and apocrypha.2

But whatever its specific content, speaking of a “Bible” as such inevitably requires reckoning with a text that has been deeply embedded and shaped within the faith and practice of the communities that have cherished it.

Ignoring this fact is then actually a historical oversight. And critical biblical scholarship undertakes precisely the task of avoiding historical oversights.

So, reminding yourself that the Bible is Scripture doesn’t run contrary to good historical method. It complements it.

3. Encounter the word of God.

If you do come to the biblical text from one of the communities that hears in it the divine word, you’ll see reading the text for its own sake as still more beneficial. Whatever else you might do with the text, either analytically or critically, reading it for its own sake can give you a precious reminder also to cherish it.

Community under the Word

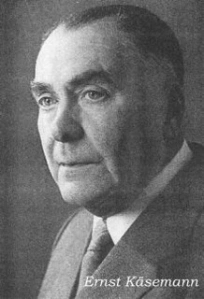

When reflecting on the question of “what are the fundamental characteristics of evangelical faith,” Ernst Käsemann suggested

The answer seems to me a simple one: in the evangelical conception, the community is the flock under the Word as it listens to the Word. All its other identifying marks must be subordinate to this ultimate and decisive criterion. A community which is not created by the Word is for us no longer the community of Jesus.… Concretely expressed, the relationship of the community and the Word of God is not reversible; there is no dialectical process by which the community created by the Word becomes at the same time for all practical purposes an authority set over the Word …. [T]he community remains the handmaid of the Word. If it makes the Word into a means to itself as an end, if it becomes the suzerain of the Word instead of its handmaid, the community loses its own life. The community is the kingdom of Christ because it is built up by the Word. But it remains so only while it is content not to assume control over the Word ….3

Being toward the Word

So much biblical scholarship involves attempts to “interpret [the Word], to administer it, to possess it.”4 This kind of activity is important and indispensable.

But confessional biblical scholars cannot afford to have only a posture over the Word as an object of study but must also sit under its authority, hear its instruction, and receive the patience, encouragement, and hope that it fosters (cf. Rom 15:4).

To be over the Word as an object of academic study involves being bent over it. And any number of forces can routinely create pressure that will bend you over even more (e.g., unavoidable but distracting demands).

Being bent over and bowed down that far can easily lead you to “collapse and fall” in overwhelm, exhaustion, and spiritual and emotional malformation. But being under the Word is a key way of finding encouragement to “rise and stand upright” (cf. Ps 20:7–8).

It gives you the chance to look up to the (metaphoric or physical) hills and contemplate where you really can find help to do what you can’t now see how you’ll be able to do (Ps 121:1–2). It brings you back to considering the reality for yourself of Jesus’s claim to provide rest for the weary and burdened as no other can (Matt 11:28–30).

4. Understand the biblical authors’ worldviews.

The task of understanding biblical authors’ worldviews presents distinctive challenges. But the challenges are hardly as absolute as thoroughgoing historicism sometimes describes them as being.

Understanding Not the Mind but the Perspective

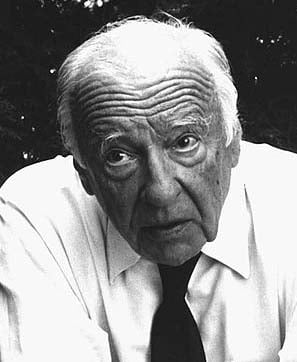

H.-G. Gadamer helpfully reflects on what it means really to understand a text, saying,

When we try to understand a text, we do not try to transpose ourselves into the author’s mind [in die seelische Verfassung des Authors] but, if one wants to use this terminology, we try to transpose ourselves into the perspective within which he has formed his views [in die Perspective, unter der der andere seine Meinung gewonnen hat]. But this simply means that we try to understand how what he is saying could be right. If we want to understand, we will try to make his arguments even stronger.5

Understanding “how what [another person] is saying could be right” can be a tall order toward those who share our same cultural contexts, or even our own homes. So, it’s certainly to be expected that similarly sustained effort will be required to understand the biblical authors.

Time Not as Problem but as Ally

At bottom, however, understanding ancient texts—whether within Scripture or not—is by no means a different kind of problem than the same one you face and navigate every day with other living people. Just like such people, ancient texts simply have their own unique demands of their interpreters.

As Gadamer also reflects,

Time is no longer primarily a gulf to be bridged because it separates; it is actually the supportive ground of the course of events in which the present is rooted. Hence temporal distance is not something that must be overcome. This was, rather, the naive assumption of historicism, namely that we must transpose ourselves into the spirit of the age, think with its ideas and its thoughts, and not with our own, and thus advance toward historical objectivity. In fact the important thing is to recognize temporal distance as a positive and productive condition enabling understanding. It is not a yawning abyss but is filled with the continuity of custom and tradition, in the light of which everything handed down presents itself to us.6

The past is, of course, not our own time. But neither is the past the wholly alien thing that thoroughgoing historicism might represent it as being.

5. See things you won’t by reading only isolated passages.

Specialization can be logical. But it shouldn’t come at the cost of not knowing other primary literature that might also prove relevant. And specialists in any given book or corpus have a real tendency toward functional ignorance of other books and corpora.

For instance, Luke and Paul shouldn’t be confused. Yet they’re both very early witnesses to the memory, faith, and practice of the Jesus movement.

So, these texts might, in principle, have just as much to say about each other as would Josephus or Philo. Readings of Luke might then feasibly enrich readings of Paul, at least as much as would readings of Josephus or Philo, and vice versa.

But literature you don’t know the contents of can’t help you. So, it’s helpful to read widely across the biblical text, as also in other primary literature outside it.

6. Correct your reading of one passage against another.

Related to this benefit is the fact that seeing things you’d otherwise miss can help you correct your interpretation of one passage against another.

Everyone understands some things better than others. And the more widely and carefully you read, the more the text has a chance to “push back” against interpretations you may have that are less than fully adequate.

Insight from Gadamer

Gadamer usefully reflects on this dynamic, asking,

How do we discover that there is a difference between our own customary usage and that of the text?

I think we must say that generally we do so in the experience of being pulled up short by the text. Either it does not yield any meaning at all or its meaning is not compatible with what we had expected. This is what brings us up short and alerts us to a possible difference in usage.

…

[A] person trying to understand a text is prepared for it to tell him something. That is why a hermeneutically trained consciousness must be, from the start, sensitive to the text’s alterity. But this kind of sensitivity involves neither “neutrality” with respect to content nor the extinction of one’s self, but the foregrounding and appropriation of one’s own fore-meanings and prejudices. The important thing is to be aware of one’s own bias, so that the text can present itself in all its otherness and thus assert its own truth against one’s own fore-meanings.7

A Personal Example

A personal example of this would be in my reading of 1 Cor 15:3a. There, Paul says he communicated to the Corinthians “ὃ … παρέλαβ[ε]ν” (“what [he] received”), but the text doesn’t specify from whom he received it.

What I’ve Suggested Previously

I’ve previously suggested in passing that this reception is “from others who also preached” the same message as Paul.8 In particular, I’ve noted that “part of what Paul likely received is a summary of the key components of the message that he rehearses in 1 Corinthians 15:3b–5.”9

This kind of interpretation is reasonably common for 1 Cor 15:3a.10 And it allows a few options for how one might understand 1 Cor 15:3 as consistent with Gal 1:12 and 2:1–10.

Options for Integrating 1 Corinthians 15:3 with Galatians 1:12 and 2:1–10

Among these are that,

- both passages refer to the same core gospel, but they speak about Paul’s reception of it in different ways and at different times. Galatians stresses his initial reception of the gospel from Jesus; 1 Corinthians mentions how Paul later had this same message echoed back to him by others besides Jesus (cf. 1 Cor 15:3, 11; Gal 2:2, 6–10).

- Galatians refers to the essential content of the gospel, which Paul received from Jesus. But 1 Corinthians is concerned with the specific form of the condensation of this gospel that appears in 15:3b–5, which Paul may have received from others besides Jesus.

- Galatians refers to the essential content of the gospel, which Paul received from Jesus. But 1 Corinthians is concerned with additional information about Jesus (e.g., details of his post-resurrection appearances in 15:6–7) that Paul might not have been privy to the details of previously but that also didn’t pertain to the core message he preached.

What I’m Now Pondering

That said, Paul also says that he “παρέλαβ[ε]ν ἀπὸ τοῦ κυρίου” (“received from the Lord”) information specific to the Eucharist’s institution (see 1 Cor 11:23–25). That specificity makes me wonder afresh about the source Paul implies for “what [he] received” in 1 Cor 15:3a. Whether and how to clearly establish that Paul’s report in 1 Cor 15:3a implies reception directly from Jesus deserves further attention.11

But for the time being, it’s good to have this question reopened. And this reopening will cause me to downgrade the specifically “receiving from others besides Jesus” interpretation of 1 Cor 15:3a from “likely” to merely possible.

7. Focus more fully and hear things you won’t by reading silently.

When you think of Bible reading, you might tend to think of silent reading. But reading the text aloud can be beneficial too.

In a group, reading aloud helps everyone follow along at the same place. If you’re reading aloud to yourself, that’s not such an upside. You always know where you are.

But if you read the text aloud—even by yourself—you engage another sense in the reading experience. By doing so, you push yourself that much more into the experience of reading.

Do you ever get distracted when “reading” a page silently? You then suddenly realize you have no idea what you’ve supposedly just seen while your mind was wandering.

By contrast, if you’re reading aloud, you’ll probably realize much quicker that your mind has started to wander when you run out of words coming out of your mouth.

Engaging another sense also gives you another chance to make connections in the text that you might overlook on paper but pick up when hearing yourself repeat the same phrase or (mis)speak a word aloud.

8. Sharpen your languages.

When you read the biblical text in its primary languages, you can hone your ability to work with these languages. You’ll get a better feel for the languages by experiencing them firsthand rather than only reading about them in a grammar.

Of course, grammars make very profitable reading on their own. 🙂 But they can’t substitute for deep, firsthand familiarity with the literature they try to describe.

If you’re reading in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek, you can even take the opportunity to read the text aloud too. That way, you can practice your pronunciation and develop your “ear” for the language.

Don’t worry too much about your choice of a pronunciation system. And don’t worry if it sounds bad or halting, especially at first. As a child, that roughness was part of your learning process for your first language. It will be here too.

But gradually, you’ll find yourself making progress. And when you hear yourself saying the text aloud, you might even see things there that you would otherwise have missed.

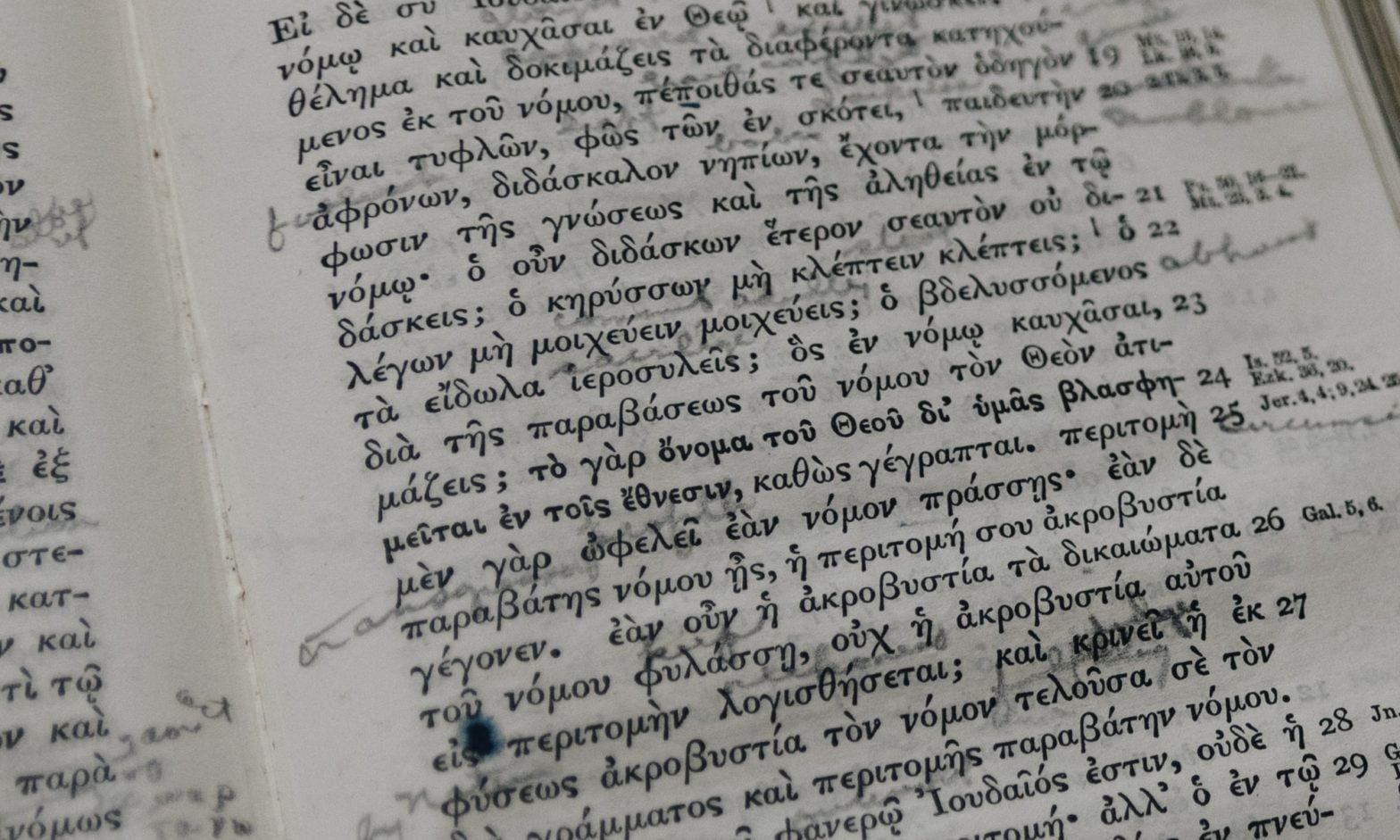

9. Find things you won’t in translation.

To communicate some things in whatever language, translators inevitably have to obscure others. This fact is wonderfully encapsulated in the Italian proverb “traduttore traditore”—”a translator is a traitor.”12

From an English translation, you might well learn about a time when a ruler of Egypt dreamed about cows. But English simply isn’t able to communicate the humorous irony involved in having פרעה (paroh) dream about פרות (paroth; Gen 41:1–2).

Many translations do a great job with rendering the core of what a passage communicates. But for the fine details both within and across passages, there’s no substitute for reading the original text.

Here also, your lack of familiarity with a biblical text’s primary language can be an asset in some ways. Generally of course, more familiarity with these languages is better. But the more familiar you are with a language, the more you’re apt also to read too quickly in that language. As you do, you might gloss over important elements in a text. But by reading the text in a primary language, you might (need to) pause long enough to consider the text more deeply.

10. Notice scribal errors.

One way to notice scribal errors is, of course, to read the apparatus in your critical biblical text. But by reading the biblical text itself, you can also notice scribal errors—namely, your own scribal errors.

For me, reading aloud particularly helps in this regard. I’ll hear myself say something. I’ll then realize what I just read aloud is related to what’s in the text but isn’t exactly the same.

These differences often fall into well-known patterns of error that copyists make during their work. And making them for yourself gives you a more firsthand appreciation for when and how these errors might arise.

This better appreciation for possible pitfalls in reading a given text can prove helpful making text-critical decisions. It also proves helpful in making you a more aware reader in the future.

11. Learn vocabulary.

When you learn biblical languages, you learn a certain amount of vocabulary that occurs frequently. But even with this under your belt, there is still a huge amount of vocabulary you don’t know.

Continuing to drill larger sets of vocabulary cards might have a place. On the other hand, you may well remember the language better by seeing and learning new words in context.

You’ll also learn new usages, meanings, and functions for the vocabulary you thought you knew. You may have learned a small handful of glosses for a word. But you’ll start seeing how that term might have a much wider range of possible meanings than the glosses you memorized.

12. Enjoy the flow of reading in the original languages.

When you consistently read Scripture in its original languages, you’ll find some of it rather heavy going. You’ll find vocabulary you need to look up or constructions that take careful thinking to sort out.

But as you keep coming back to the text (without cheating), your ability to cope with its demands will gradually improve. And as it does, you’ll hit stretches where you know most (or all) of the vocabulary and where the syntax pretty readily makes sense.

In such situations, the challenge the text presents roughly equals your ability to read it. That balance between challenge and skill is one of the preconditions for the “optimal experience” of “flow.”13

When this happens, you get to enjoy the quiet thrill of

- reading a section of text with comparative fluency,

- reading larger chunks at a time, and just maybe,

- getting so immersed in the reading that you lose track of time.

Don’t Settle for the Cliché

Unfortunately, biblical scholars who don’t have a regular discipline of Bible reading are common enough to be cliché.

Whether you find yourself in this boat or whether you’d just like to join others who are actively in the text, consider joining my students and me this term in our readings of the biblical text.

Every term, we do a daily Bible reading exercise together. If you’re working in the original languages, I’ve scaled the readings to be short enough to complete without taking too much time out of your day. But the reading plan will work whether you’re using a translation or working from the biblical text in its original languages.

It would be wonderful to have you join us. To get started, just drop your email address in the form below. You’ll then get a message delivering this term’s readings. And you’ll be ready to pick up in the biblical text right where my students and I are.

Looking forward to reading with you!

Header image provided by Kelly Sikkema. ↩

For further discussion, see my “Rewriting Prophets in the Corinthian Correspondence: A Window on Paul’s Hermeneutic,” BBR 22.2 (2012): 226–27. ↩

Ernst Käsemann, New Testament Questions of Today, trans. W. J. Montague and Wilfred F. Bunge (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1969), 261–62. The headshot comes courtesy of Nick Nowalk. ↩

Käsemann, New Testament Questions, 261. ↩

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, ed. and trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall, 2nd ed. (affiliate disclosure; New York: Crossroad, 1989; repr., London: Continuum, 2006), 292; Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, ed. and trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall, 2nd ed., Bloomsbury Revelations (affiliate disclosure; London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2013), 303; italics added. The German insertions are drawn from Hans-Georg Gadamer, Wahrheit und Methode: Grundzüge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik (affiliate disclosure; Tübingen: Mohr, 1960), 297. The headshot comes courtesy of the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ↩

Gadamer, Truth and Method, 308. ↩

Gadamer, Truth and Method, 2nd ed., 280, 282; italics added. ↩

J. David Stark, “Understanding Scripture through Apostolic Proclamation,” in Scripture First: Biblical Interpretation That Fosters Christian Unity, ed. Daniel B. Oden and J. David Stark (affiliate disclosure; Abilene, TX: Abilene Christian University Press, 2020), 56. For more about Scripture First, see “6 Ways to Make Scripture First.” For more about my essay, see “Behind the Scenes of ‘Understanding Scripture through Apostolic Proclamation’.” ↩

Stark, “Apostolic Proclamation,” 56. ↩

E.g., Roy E. Ciampa and Brian S. Rosner, The First Letter to the Corinthians, PilNTC (affiliate disclosure; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2010), 745; Joseph A. Fitzmyer, First Corinthians: A New Translation with Introduction and Commentary, AB 32 (affiliate disclosure; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008), 545–46; Richard B. Hays, First Corinthians, Interpretation (affiliate disclosure; Philadelphia: Westminster John Knox, 1997), 254–55; Heinrich August Wilhelm Meyer, Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians, ed. William P. Dickson, trans. D. Douglas Bannerman and David Hunter, 2 vols. (affiliate disclosure; Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1879), 2:42; cf. F. F. Bruce, The Epistle to the Galatians: A Commentary on the Greek Text, NIGTC (affiliate disclosure; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1982), 88–89; A. T. Robertson and Alfred Plummer, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, 2nd ed., ICC (affiliate disclosure; 1914; repr., Edinburgh: T&T Clark, 1929), 333. ↩

Cf. C. K. Barrett, The First Epistle to the Corinthians, BNTC (affiliate disclosure; London: Continuum, 1968), 337; John Calvin, Commentary on the Epistles of Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians, trans. John Pringle, 2 vols., Calvin’s Commentaries (affiliate disclosure; Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society, 1848–1849), 2:9. ↩

For making me aware of this proverb, I’m grateful to Moisés Silva. ↩

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, Modern Classics (affiliate disclosure; New York: Harper Perennial, 1991), 72–77. ↩

Leave a Reply